Lisa and Quarantine: How Coronavirus Affects the Lives of People with Autism

Mother’s Day is a very important and widely celebrated holiday in the United Kingdom. For a long time it was not a very pleasant day for me. This year, it coincided with World Autism Awareness Day on April 2. I don’t know about other countries, but in the U.K. stores are rolling out boxes of flowers, greeting cards, chocolate and sparkling wine in the shopping aisles, while fundraisers for various autism support events are being held outside stores and online. Two events in two parallel worlds that may or may not intersect. On Mother’s Day (the last Sunday in March), young children make crafts and cards for their mothers, and kindergartens host festive tea parties.

Many mothers of children with developmental disabilities in the UK feel sad on Mother’s Day because they do not have such a widely recognized holiday. Adult children, along with dad or other family members, relieve mom of all household chores. And of course, it is customary to visit grandmothers, as mothers must also congratulate their beloved mothers on the holiday. In the early years, when I found out that my oldest daughter, Lisa, had autism, she painfully wanted me to be “like everyone else.

Mothers of special children often want to receive the complete set of stereotypes during the holidays, like the flowers and greeting cards in stores. So that she not only brings home from kindergarten a touching string of beads made of colored dry noodles at the teacher’s insistence, but also understands why. So that she can sing a song about her mother, recite a poem, give her a hug, and enjoy a happy holiday. So I wanted to get a complete set of stereotypes, like those flowers and postcards in the stores, because they seem the most desirable and unattainable when a child at three or four is practically nonverbal, still in diapers, and sucking on a pacifier. Mother’s Day seemed like a special annual milestone to me: “I’ve been a good mother all year, so I deserve a holiday, gifts, and adoration.” I was constantly plagued by feelings of guilt. It seemed to me that I was not doing enough for my daughter, that she was progressing slowly, and that the vacation was not yet due for me. I was especially upset about the toilet mishaps that day – can’t my child be like others, at least for one day? I understand where the feeling of being a bad mother comes from. I remember the puzzled and judgmental looks of other mothers with their wonderfully developing babies during playtime at the daycare center.

Parents, though not very experienced, cannot filter information and feel guilty that their child’s autism does not go away. I remember the feeling of being a bad mother when other children are busy with music, dancing, gymnastics, riding bikes and scooters while my daughter is having a tantrum in the bus aisle. When my daughter screamed and threw tantrums, took toys from everyone, refused to move cars in a row, scratched and shoved other children, and even bit an innocent little girl who spoke very well for her age and just wanted to make friends. We explain quickly, simply, and clearly what happened, why it matters, and what happens next. The number of offers should remain: episodes. End of story. Podcast advertising. Finally, when other grown babies sit in the café and eat by themselves with their hands, spoons, it doesn’t matter, the main thing is that they do it themselves. And I hastily stuff my daughter with packaged purées and distract her with a pile of books (always in strict order), otherwise she won’t eat. This complex of being a bad mother is often intensified when a child receives a diagnosis. Oddly enough, the special needs parenting community can sometimes be quite judgmental and cruel (not to mention internally self-critical and self-doubting). As parents go through the stages of grief and come to terms with the idea of raising a child with special needs, they are bombarded from all sides with stories about the wonders of early intervention in autism: how diet, vitamin supplements, creating an appropriate environment, specific methodologies (and among them there will always be the “one and only”) will make the impossible possible: the child’s diagnosis will be removed or “no one will believe he has autism”. And parents (especially mothers), who are not very experienced, cannot filter the information and blame themselves for the fact that their child’s autism does not disappear. For example, for a long time I couldn’t forgive myself for sending my daughter to a specialized school and considered it my failure as a mother. Fortunately, with age, the feeling of being a bad mother, if it does not disappear completely, manifests itself much less often. I understand that there are no miracle cures, and that a specialized school may be a much better option for education than an overcrowded regular school. I understand that the spectrum of autism is so wide and varied that each child’s situation is unique and it makes no sense to look for universal solutions. And I do everything possible for my daughter that I am currently able to do. So I am not such a bad mother.

A specialized school can be a much better option for education than an overcrowded regular school. I know that many mothers of children with special needs in the UK still experience some sadness on Mother’s Day because they do not have such a widely celebrated holiday. Although it seems to me that Mother’s Day should be a day of respect for special mothers. Because every day, year after year, these mothers do something amazing. First of all, it is a daily physical feat: changing diapers, toilet training (with all its unappetizing details), and changing clothes – these are not just short-term childhood tasks, but rather the duties of parents for many years, sometimes a lifetime. This is a daily emotional burden – strong tantrums and increased anxiety of the child, his constant talking about the same things, situations where conflicts between the child and the surrounding world occur, can be very exhausting and emotionally draining. It is constant self-learning, searching for good methods, doing homework, long trips to “necessary specialists” or specialized clubs, which are not available in every area.

It is endless reading of doctors’ conclusions, reports from teachers and social workers, letters from the district education office. For many parents, it is a struggle with the bureaucratic system, courts and appeals regarding the educational institution and the child’s support plan. Finally, this is a constant saving, because the meetings with specialists provided by the government are usually categorically insufficient. Private lessons are quite expensive: a session with a speech therapist or fine motor specialist costs an average of £70 per hour, while a consultation with a behavior analyst starts at a few hundred pounds. The financial burden is compounded by the fact that many mothers have to reduce their work hours or even quit their jobs to care for a child with developmental needs. But the heroics do not end there! Special Moms volunteer their time, create charitable organizations, write books and textbooks, and share their children’s stories with the world. Thanks to the mother of a boy with autism named Joe, autism has been widely discussed in the United Kingdom. In October 1961, Joe’s mother, Helen Allison, appeared on the BBC’s Woman’s Hour and spoke about her child’s unique characteristics. After the show, Helen received several thousand letters from other parents who were in the same situation and wanted help. This was the beginning of the UK’s largest charity supporting families affected by autism, the National Autistic Society. In the area where I live, there is also a charity organization that is successfully run by mothers of children with autism. The clients of this organization are also 99% mothers. Back to Mother’s Day. It’s been three years since I didn’t feel like a stranger on this holiday of life. With my younger daughters, I managed to receive all the traditional songs, tea parties and poems, as well as homemade gifts. But this year’s holiday was special. Because my older daughter, Lisa, did what I had been waiting for many years to do.

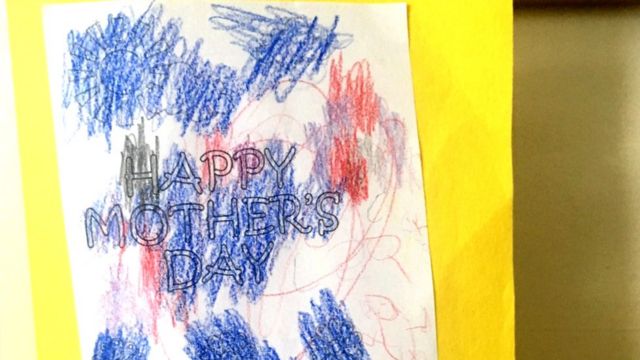

The postcard Lisa made for her mom. After school, Lisa opened her bag, handed me a postcard, and proudly said, “I made it myself.

Anna Cook is a journalist who has lived in England since 2007. Her eldest daughter was diagnosed with autism at the age of three.